By Stanley Solamillo

Black Women’s History: Euro-African Marriages in Ghana and the Gold Coast – New Narratives

A 1915 photograph by Basel Mission of French colonial officers from the Ivory Coast with their Ghanaian wives and children, used as the cover illustration for Carina E. Ray’s Crossing the Color Line: Race, Sex, and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana, Ohio University Press/Swallow Press, 2015. Photo Courtesy Ohio University Press/Swallow Press.

The infamous Gold and Slave Coasts of West Africa conjure up images of European brutality beyond belief that by now every student of Black History knows by rote. It is from those shores that 12.5 million African men, women, and children who had been corralled, tortured, raped, and starved, were sent on the “largest forced migration in history” to the Americas as slaves. The Atlantic (or Transatlantic) Slave Trade (1502-1867), whose roots lay in an Iberian Slave Trade (1440-1640) that brought thousands of Africans to a European peninsula of the same name, produced some 30 “forts, castles, and trading posts” that were established along the coasts. These served as the points for collection and/or departure for thousands of persons per year through portals now known as “Doors of No Return.”

Many of these settlements were initially built as outposts to acquire gold and other commodities (hence the foreigners’ name of “Gold Coast”). Then after the slave trade surpassed everything in profitability (gaining for the region the moniker of the “Slave Coast” by 1750), they were often fought over, surrendered or purchased, and operated by a succession of European companies from eight nations. They included Portugal, Spain, England, Sweden, Holland, Denmark, France, and Prussia. The narratives about Europe’s nearly 400-year venture in human trafficking are numerous and rightly focused on the unfathomable scale and violence of the trade and its African victims.

However, what has recently come to light (for American scholars) and introduces a new narrative into the existing body of work on this horrific period is the acknowledgement of a 300-year tradition of Euro-African marriages that appears to have co-existed in proximity to some of those very same “forts, castles, and trading posts.” The most recent of these histories was written by Pernille Ipsen and published under the title: Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast (2014).

Ipsen conducted her research primarily in Danish records associated with Fort Christiansborg (Osu Castle) that were produced over a 150-year period (1700-1850). The source material included government records of the Danish administration at the fort and related correspondence to trading companies and to the Danish crown; records and correspondence between chaplains at the fort, the bishop of Zealand in Copenhagen, and Danish companies; as well as contemporary Northern European travel accounts.

While focusing on the story of a free Ga-speaking woman named Severine Brock, who had been born and raised in Osu (Accra) and who married the last Danish governor of the fort, Edward Carstensen, Ipsen discovered that women in Brock’s family as well as other free women had been marrying Danes for five or more generations. The Euro-African (Ga-Danish) society that the women created along with their children was a hybrid intermediary between the majority African and minority European outpost societies. Many became quite wealthy and acquired markers of prestige in position, attire, domicile, and education for their children. However, Denmark outlawed the slave trade in 1803 and later sold the fort to the British in 1850.

Britain initiated its formation of the British Gold Coast later in 1867 when it seized British trading company lands, combined them with the Danish holdings from 1850, acquired Dutch-held properties (such as Elmina Castle) in 1872, and officially designated the country as a colonial possession in 1874, following conclusion of a treaty with the Ashanti (Asante) people in that year. In typical imperial fashion, Britain waged five wars to pacify the Ashanti people (the largest ethnic group in the country) in 1822-24, 1873-74, 1893-94, 1895-96, and 1900.

Under British rule (1874-1957) intermarriage between European men (especially British officers) and African women became problematic. The colonial government attempted to curtail it with a so-called Marriage Ordinance in 1887 and then banned it outright for government officials and the military in 1907 by decree. The government’s actions essentially drove legitimate unions underground and invited potential abuse from “temporary marriages” with other Europeans such as some of the compatriots of the French officers pictured in the 1915 photograph. Although the European slave trade had been abolished, the anti-miscegenation bias and resulting segregation that supplanted it was in conflict with African customs of the pre-colonial period and Ga-Danish society. Ipsen offered in explanation that: “In European colonies, interracial marriage was a threat to European control and was therefore prohibited and policed…”

In a second book entitled, Crossing the Color Line: Race, Sex, and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana (2015), Carina E. Ray used court records, government documents, newspapers, and oral history interviews to investigate the British colonial government’s increasingly hostile positions on race and sexuality along with its impact on intermarriage in the colony (and abroad) during the latter period. She noted that as late as 1915 some African writers such as Atu, a columnist for the indigenous Gold Coast Leader was so outraged by the government’s policies that he stated the unthinkable when he lamented the loss of the “Dutch Times” when “conditions were wholly different [and] marriage relations between black and white [were] honest…” Ray described the advent of segregation and race-based discrimination that was implemented in the early twentieth century and provided closure with details of an incident that occurred in the aftermath of the country’s independence in 1957 (which was also presented in the book’s introduction).

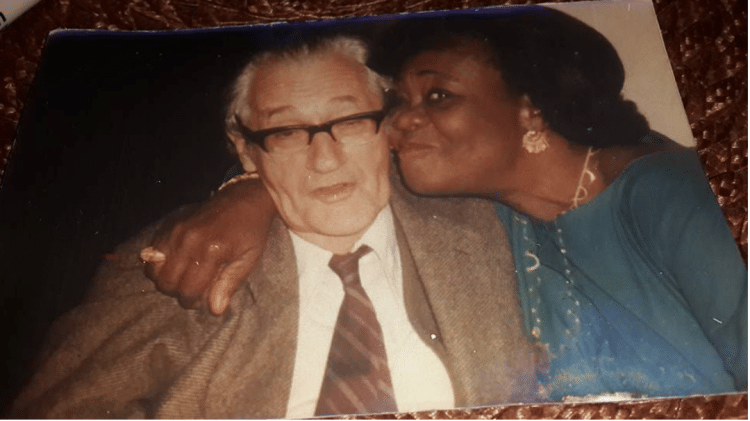

In 1961, a former British government official named Brendan Knight, who had been retained by the new Ghanaian state to assist in the transition from colony to independent nation, was notified that he was scheduled for termination from civil service. Earlier in 1945, in defiance of the colonial decree, Knight had married a Ghanaian woman named Felicia. In 1961, his wife saved his job and their family of five children when she successfully pleaded their case with then president Kwame Nkrumah. The president issued a special dispensation for Knight based upon the fact that he “[was] married to a Ghanaian and ha[d] five children with her, [and that] all of whom ha[d] been brought up as Ghanaians.”

Both Ipsen and Ray’s books merit reading because they provide new narratives about two periods that have been widely studied for decades. They also inform us that our histories are much more complicated and inter-connected than we might imagine. Such histories also contain as much evidence of massive cruelty and inhumanity as they do otherwise. They also provide new insights into the differences with which Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast viewed interracial marriage, how the British colonial government, perpetually fearful of “race-mixing,” contorted religion, public law, and custom to keep the “races” separate, and how various groups—African and European—decided to choose otherwise.

Brendan and Felicia Knight, Accra, Ghana (n.d.). Brendan, a district commissioner in the Gold Coast colonial government, married Felicia in 1945 in defiance of a colonial decree that had been in effect since 1907. In 1961, Felicia successfully prevented his termination during the Africanization of the country’s civil service by pleading their case with then president Kwame Nkrumah. Photo Courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sources:

Ipsen, Pernille. Daughters of the Slave Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriages on the Gold Coast. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2014.

Diarra, Lilian, “Ghana’s Slave Castles: The Shocking Story of the Ghanaian Cape Coast.” The Culture Trip.

https://theculturetrip.com/africa/ghana/articles/ghana-s-slave-castles-the-shocking-story-of-the-ghanaian-cape-coast/ Accessed February 19, 2016.

Magaziner, Dan. “Valentine’s Day Special! On love, race and history in Ghana.” February 14, 2016. Africacountry.com.

https://africasacountry.com/2016/02/love-race-and-history-in-ghana/ Accessed February 20, 2016.

Priestley, Margaret. West African Trade and Coast Society: A Family Study. London: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Ray, Carina. Crossing the Color Line: Race, Sex, and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Wheat, David. “Iberian Roots of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1640.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/origins-slavery/essays/iberian-roots-transatlantic-slave-trade-1440–1640 Accessed February 21, 2016.

Worchester Cathedral Library. “Fort Christiansborg and the Forging of Modern Ghana.”

https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2015/08/24/fort-christiansborg-and-the-forging-of-modern-ghana/ Accessed February 21, 2016.